curves~behind.bitcoin

a hands-on tour of secp256k1, ecdsa and schnorr signatures

Bitcoin isn't "secured by passwords". It's secured by math.

And at the center of that math is one of the most elegant structures in cryptography:

an elliptic curve.

- What even is a field or a curve?

- How does 256-bit randomness become a public key that nobody can reverse?

- How are signatures used to verify transactions?

If you're more hands-on you can open this notebook which has code to follow along.

Why elliptic curves?

Cryptography needs mathematical structures where certain operations are easy in one direction but practically impossible to reverse. Before elliptic curves, systems like RSA used the difficulty of factoring large numbers. But there's a catch: as computers get faster, you need exponentially larger keys. A 256-bit RSA key is trivially breakable today.

Elliptic curves give us something special: a group where the discrete logarithm problem is much harder per bit of key size. A 256-bit elliptic curve key provides roughly the same security as a 3072-bit RSA key. This means:

- Smaller keys (32 bytes vs 384 bytes)

- Faster operations

- Smaller signatures

- Less bandwidth and storage

The "magic" is that while you can efficiently compute (multiply a point by a scalar), there's no known shortcut to recover from and . The group structure scrambles the point through billions of additions in a way that appears random, and unlike integer logarithms, there's no equivalent of a "slide rule" that lets you work backwards.

From continuous geometry to discrete arithmetic

Bitcoin uses an elliptic curve known as secp256k1.

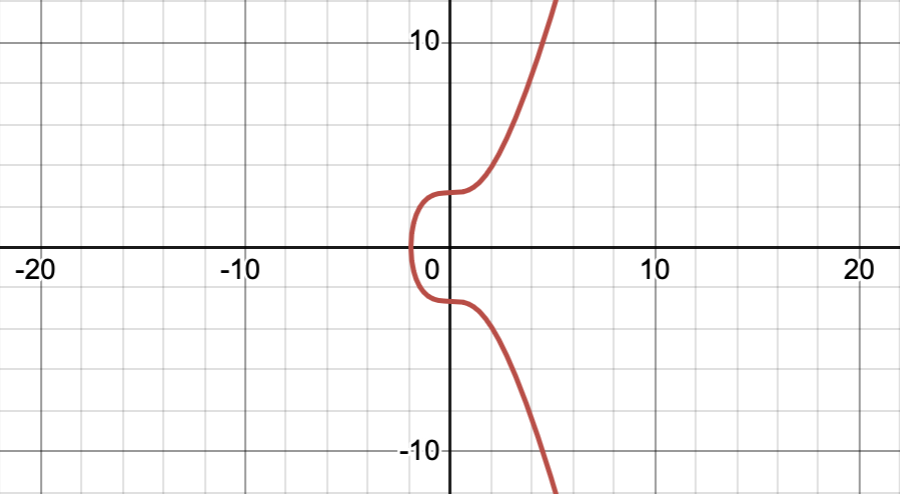

On a continuous plane (real numbers), it looks like a smooth curve:

We observe that in an elliptic curve, there are two y-values for a given x. This observation will come in handy later.

Bitcoin curves are modular and discrete

In Bitcoin, we don’t use real numbers at all.

Instead, all numbers live inside a finite field — integers modulo a large prime .

A finite field (where is prime) is the set:

where addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are all done modulo .

Why must be prime?

Because when is prime, every non-zero element in has a multiplicative inverse:

That means division always works.

This is what makes a proper field — and elliptic curve formulas rely heavily on division.

The curve equation modulo

Bitcoin’s curve is not the real-number curve that we drew above .

It is the modular version:

That single change — doing everything mod — completely changes the geometry:

- you only get a finite set of valid integer points

- there is no smooth curve anymore

- arithmetic wraps around at

- there are no fractional coordinates

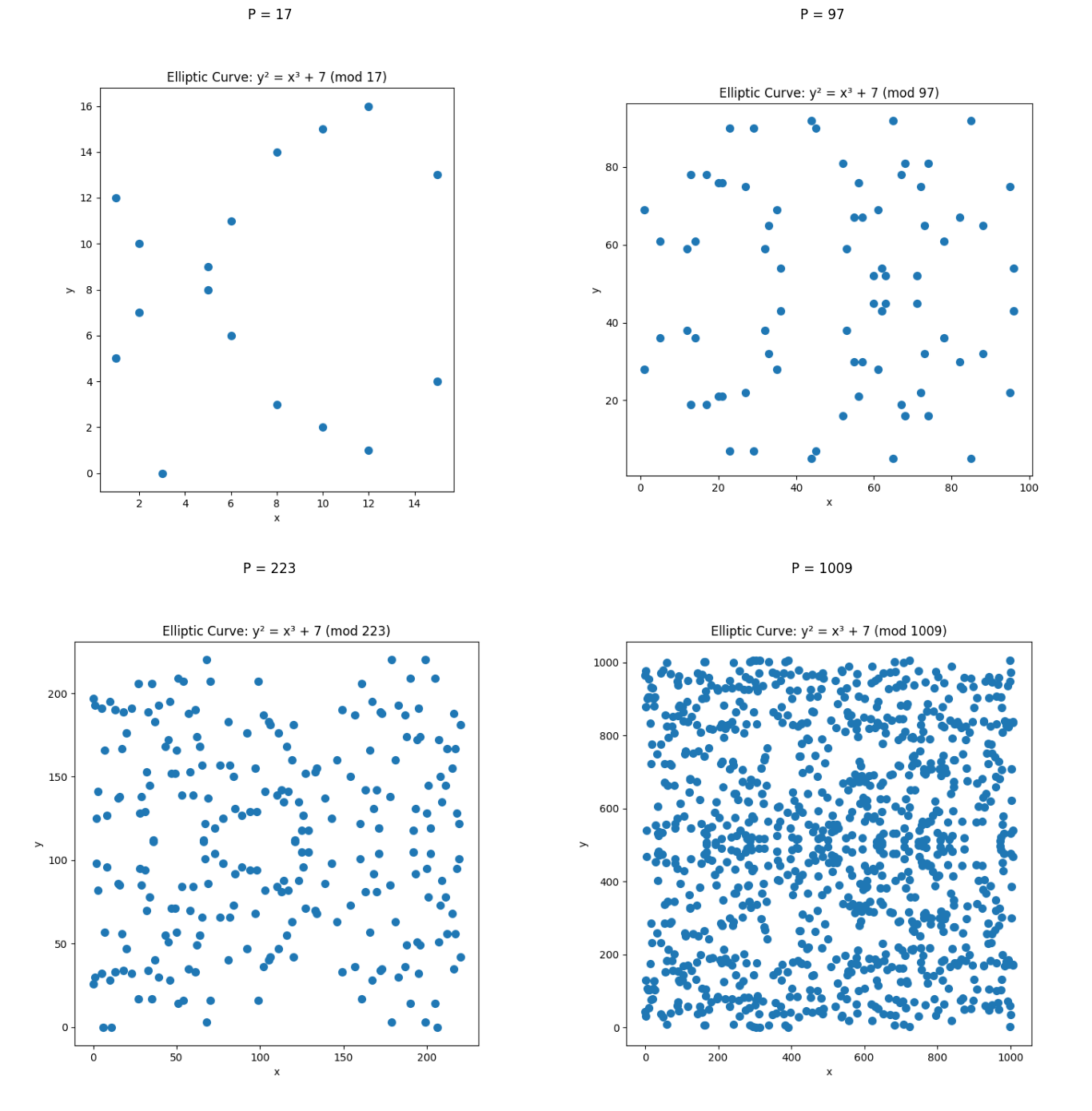

So what does the curve look like mod ?

Instead of a continuous curve, you get a cloud of discrete points:

At this point, the curve has boiled down into a finite set of points — and now we can define algebra on them. Even though it looks random, this set of points forms a group with a special addition rule. That group structure is what Bitcoin uses for public keys and signatures. Your public key is in fact, one of those points!

Terminologies: Curve, Point, and Scalar

To build Bitcoin signatures from scratch, we’ll use a few core objects and operations. All of this is discussed in the context of secp256k1.

1. Prime field modulus:

All coordinate math is defined over finite field :

- valid coordinates are integers in the range

- arithmetic “wraps around” mod

The same can be represented in:

Hex = 0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffefffffc2f

Dec = 1157920892373161954235709850086879078532699846656405640394575840079088346716632. Any point:

A point is a pair that satisfies the curve equation mod . Therefore, it's valid if and only if:

3. Point at infinity:

There’s a special point called the point at infinity, written . It behaves like the identity element of addition:

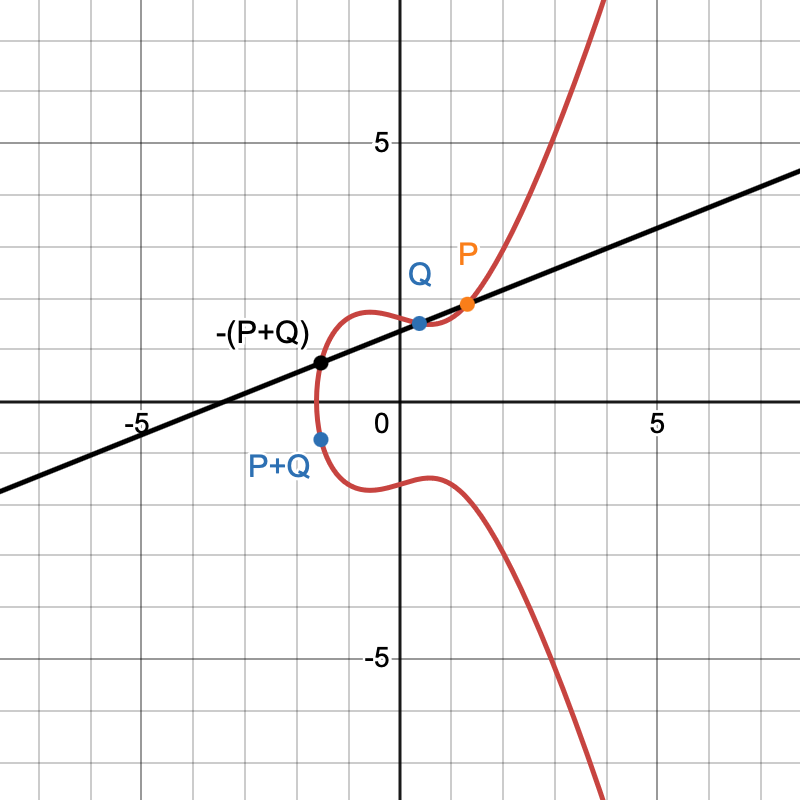

4. Point addition:

Elliptic curve points can be “added” using a special algebraic rule. This addition has important properties:

- it stays on the curve (closure)

- it is associative

- there is an identity element

This is what makes elliptic curve points form a group. The algebraic process graphically is shown below:

5. Point negation / inverse:

Every point has an inverse:

, such that

6. A scalar:

A scalar is just an integer used to repeatedly add a point.

We use scalars in two places:

- mod for field arithmetic (coordinates and slopes)

- mod for group scalars (private keys and signatures)

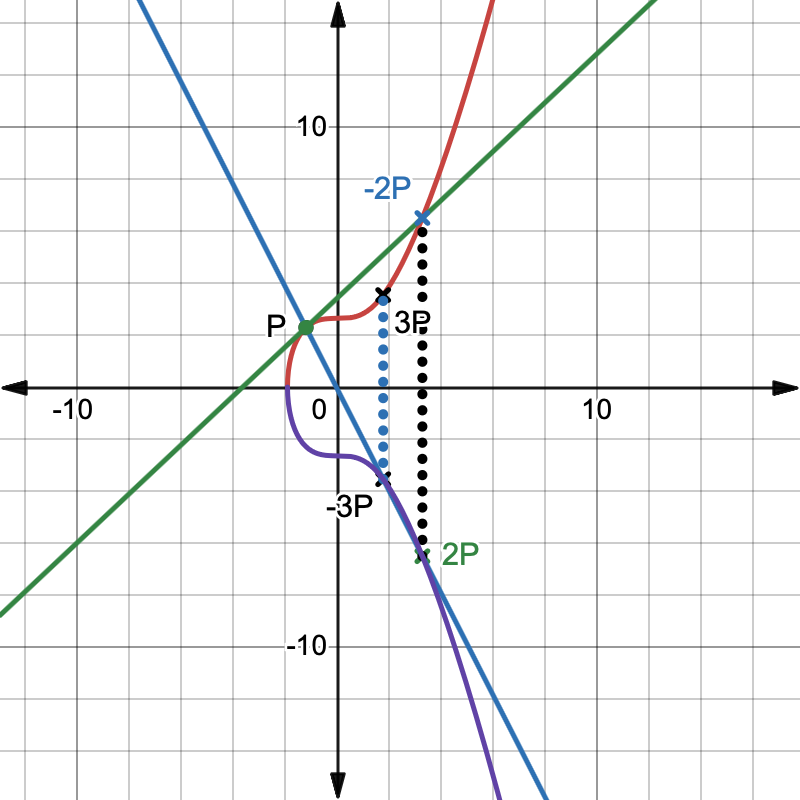

7. Scalar multiplication:

Scalar multiplication means:

This is the core operation behind Bitcoin keys:

- easy to compute forward

- hard to undo (discrete log problem)

8. Generator point:

The generator point is a fixed point on the curve chosen by the standard. It generates the subgroup used in Bitcoin.

Gx = 55066263022277343669578718895168534326250603453777594175500187360389116729240

Gy = 32670510020758816978083085130507043184471273380659243275938904335757337482424In practice, private key is a scalar while public key is the point .

9. Group order:

If you add to itself times, you get the identity point.

The number is called the order of the subgroup generated by .

Hex = 0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffebaaedce6af48a03bbfd25e8cd0364141

Dec = 115792089237316195423570985008687907852837564279074904382605163141518161494337Bitcoin requires scalars to be in this range, and most signature math happens modulo .

Generating a Public/Private Keypair

Private Key: Any scalar

Corresponding public key: , a point on the secp256k1 curve.

d = secrets.randbelow(n)

P = d * GThis operation is easy to compute, but hard to reverse. Mathematically, given and , it's infeasible to compute , where .

SEC1 Public Key Serialization (used in ECDSA)

The points are generated modulo which is in 256 bits or 32 bytes.

Therefore, x or y coordinate values will be of 32 bytes.

Uncompressed Serialization (65 bytes)

04 || x(32 bytes) || y(32 bytes)Compressed Serialization (33 bytes)

For a given x, there can be ONLY two values of y, because

(03|02) || x(32 bytes)

03 = odd y

02 = even yBIP340 X-Only Public Key Serialization (used in Schnorr/Taproot)

BIP340 enforces a canonical rule:

The public key point is always interpreted as the point with even

Thereby, if public key has an odd y value ( is odd), then the private key is negated to , giving which has even .

The serialization here will only be the x value, so 32 bytes.

x(32 bytes)Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA)

ECDSA is the signature scheme Bitcoin used from day one (and it’s still widely used today). It lets you prove:

I know the private key corresponding to public key ,

without revealing .

ECDSA Signing Algorithm

The signer has:

- Private Key

- Public Key

- Message Hash (For Bitcoin, this is the transaction sighash)

The signature is the pair

Step 1: Generate a secret nonce

- must be unpredictable - must never repeat - must remain secret

In production Bitcoin, this is done deterministically using RFC6979

Step 2: Compute the nonce point

Take its x-coordinate:

Step 3: Compute the signature scalar

The signing formula is:

The final ECDSA signature is:

def ecdsa_sign(z: int, d: int, G: Point) -> Tuple[int, int]:

"""

Sign a message hash interpreted as integer z.

Returns (r, s) as integers in [1, n-1].

"""

n = G.curve.n

if n is None:

raise ValueError("Curve must have order n")

if not (1 <= d < n):

raise ValueError("Invalid private key d")

z = z % n # message should also be mod n

while True:

# Random Nonce is fine for learning but not production

# because what if nonce reused because of randomness?

# k = secrets.randbelow(n)

# RFC6979 Deterministic Nonce

k = rfc6979_generate_nonce(d, z, n)

R = k * G

if R.is_infinity(): continue

r = R.x % n

if r == 0: continue

k_inv = Scalar(k, n).inv().value

s = (k_inv * (z + r * d)) % n

if s == 0: continue

# The signature is NOT a point, just a pair of values

return (r, s)ECDSA Verification Algorithm

The verifier has:

- signature

- message hash

- public key

They want to verify the signature without knowing .

Step 1: Range checks

Otherwise reject

Step 2: Compute inverse of

Step 3: Compute two scalars

Step 4: Reconstruct the point

Reject if .

Step 5: Compare x-coordinate

The signature is valid iff

def ecdsa_verify(z: int, sig: Tuple[int, int], P: Point, G: Point) -> bool:

"""

Verify ECDSA signature (r,s) for message hash integer z against public key P.

"""

r, s = sig

n = G.curve.n

if n is None:

raise ValueError("Curve must have order n")

if P.is_infinity() or (P.curve != G.curve):

return False

if not (1 <= r < n and 1 <= s < n):

return False

z = z % n # message should be mod n

s_inv = Scalar(s, n).inv().value

u1 = (z * s_inv) % n

u2 = (r * s_inv) % n

X = (u1 * G) + (u2 * P)

if X.is_infinity():

return False

return (X.x % n) == rECDSA Problems

Bitcoin, historically, had to deal with two classes of problems.

1. Nonce reuse leaks the private key

Now, suppose you sign and with the same nonce .

Subtract:

And once is known,

Private Key

Why Deterministic Nonces?

If is generated randomly, even a tiny flaw in the RNG (biased bits, predictable state, or VM snapshot reuse) can leak the private key. RFC6979 removes this risk entirely by deriving deterministically from the private key and message: .

This means:

- Same always produces the same — no randomness needed

- Different messages produce different values — no reuse

- The nonce is unpredictable to attackers who don't know

2. Signature Malleability

If is a valid ECDSA signature, then is also valid.

r, s = sig = ecdsa_sign(z, d, G)

assert ecdsa_verify(z, (r, s), P, G) # expected to pass

assert ecdsa_verify(z, (r, n - s), P, G) # NO ERROR!Reasons Bitcoin moved away from ECDSA (towards Schnorr / Taproot)

1. Transaction ID Malleability: (pre- SegWit)

Before SegWit, the transaction ID was computed as:

and the serialization included scriptSig, which contains the signature bytes.

So any mutation to signature bytes could change the txid even though the spend remained valid.

a) DER encoding malleability (non-canonical encodings)

- The same mathematical ECDSA signature (r, s) could be encoded in multiple valid (but non-canonical) ways in DER

- This allowed third parties to mutate signature bytes, and therby mutate txid

It was fixed by BIP66 (Strict DER encoding) (consensus rule).

b) s-value malleability (high-s / low-s)

For any valid signature (r,s), this is also valid: (r, n - s)

This produces a different signature that still verifies, again allowing txid mutation pre-SegWit.

Mitigated by enforcing low-S signatures as policy/standardness (often discussed in context of BIP62), and later enforced more strictly for SegWit spends.

c) SegWit solved it structurally

SegWit moved signatures into the witness, so:

- txid no longer commits to signatures

- malleability no longer breaks txid-based chaining

Fixed by SegWit (BIP141) at the protocol level.

2. Nonce Fragility / Leaking Private Key (discussed above)

3. No clean key aggregation

ECDSA's multiplicative structure () doesn't compose nicely. If Alice and Bob want to create a joint signature, they can't simply add their individual signatures together.

Schnorr's linear structure () is fundamentally different. If Alice signs with and Bob signs with , then is a valid signature for the aggregated key .

This linearity enables protocols like MuSig2, where multiple parties can create a single signature that's indistinguishable from a regular signature — enabling efficient multisig, atomic swaps, and more.

4. Additional malleability vectors

Beyond the malleability discussed above, ECDSA has other subtle malleability issues:

- The same values can sometimes be valid for different messages if values collide after mod reduction (extremely rare but theoretically possible)

- Implementation bugs around DER encoding created additional attack surface

Schnorr's design eliminates these by construction: the even- requirement and the way the challenge hash commits to the full message remove ambiguity.

5. No efficient batch verification

When a Bitcoin node receives a block with hundreds of transactions, it must verify hundreds of signatures. With ECDSA, each verification requires separate elliptic curve operations.

Schnorr verification is a linear equation: check that , or equivalently, .

For multiple signatures, you can combine these checks:

With random coefficients (to prevent cancellation attacks), this becomes a single multi-scalar multiplication — which is much faster than separate verifications. Batch verification can speed up block validation by 2-3x.

Schnorr Signatures (BIP340)

Schnorr signatures are what Bitcoin uses for Taproot outputs. They are cleaner, more structured, and more composable.

Schnorr signatures look like:

where:

- is the x-coordinate of nonce point

- is a scalar modulo

Schnorr Signing Algorithm

The signer has:

- Private Key

- Public Key

- Message (32 bytes)

Step 1: Compute public key and enforce even-y

If is odd, replace and so that is always even.

Step 2: Generate nonce deterministically

BIP340 uses tagged hashes with optional aux randomness:

Step 3: Compute nonce point

If is odd, replace and so that is always even.

Step 4: Compute challenge

Step 5: Compute signature scalar

The Schnorr signature is , serialized as

rx(32 bytes) || s(32 bytes)Schnorr Verification Algorithm

The verifier has:

- x-only public key

- signature

- message

Step 1: Range checks

Step 2: Lift x-only public key

Compute : solve and choose the even .

Step 3: Compute challenge

Step 4: Reconstruct nonce point

Reject if .

Step 5: Final checks

Signature is valid iff is even and .

You can take a look at the implementation of Schnorr Signatures in the notebook.

Tagged Hashes in BIP340

BIP340 uses tagged hashes for domain separation:

BIP0340/auxBIP0340/nonceBIP0340/challenge

Schnorr vs ECDSA: No Malleability

In ECDSA, and both verify.

In BIP340 Schnorr, signatures are canonicalized using the even- requirement on , so the "flip " trick does not produce a second valid signature.

A Note on Quantum Computing

Everything in this post assumes classical computers. A sufficiently powerful quantum computer running Shor's algorithm could solve the discrete log problem in polynomial time, breaking ECDSA and Schnorr alike.

How worried should we be?

- Current state: As of 2026, the largest quantum computers have a few thousand qubits. Breaking secp256k1 would require millions of stable, error-corrected qubits.

- Timeline estimates: Experts disagree wildly — some say 10 years, others say 30+, some say never at scale.

- Bitcoin's exposure: Only public keys that have been revealed (by spending) are vulnerable. Addresses that have never spent are protected by the hash function layer (RIPEMD160 + SHA256), which quantum computers don't break as efficiently.

- Mitigation: Post-quantum signature schemes exist (lattice-based, hash-based) and could be added to Bitcoin via soft fork if quantum computers become a real threat.

The cryptographic community is actively researching post-quantum alternatives, but for now, elliptic curves remain secure against all known attacks.

Takeaways

The security of Bitcoin rests on a beautiful mathematical foundation: the difficulty of reversing scalar multiplication on elliptic curves. From a 256-bit random number (your private key), we derive a public key that's trivial to compute but impossible to reverse. Signatures prove you know the private key without revealing it, using the clever trick of committing to randomness before being challenged.

ECDSA served Bitcoin well for over a decade, but its multiplicative structure created subtle problems: fragile nonces, signature malleability, and no path to aggregation. Schnorr's linear design () elegantly solves these issues while enabling new capabilities like efficient multisig and batch verification.

Key concepts:

- for coordinates/slopes, for private keys/signature scalars

- Modular inverse exists for all non-zero values in both fields

- A point has a group inverse , not a modular inverse

- Recovering from is the Elliptic Curve Discrete Log Problem (infeasible)

- ECDSA nonce failure is catastrophic (leaks private key)

- Schnorr signatures are smaller, canonical, and better for aggregation

- Tagged hashes provide domain separation

auxis signer-only randomness to harden nonce generation